Was Mary Cavillon thinking about her children when she entered the dwelling-house of William Dean in the West End of London on the 5th of December 1810? Did she contemplate the consequences of her carefully laid plans going awry? Perhaps she did, but Mary’s plans could not have gone more awry than they did that day.

In December 1810, bleak weather descended upon England, culminating in a tornado on the fourteenth day that tracked from Old Portsmouth to Hampshire, flattening houses in its wake. The weather would surely have impacted London where Mary lived, just sixty-six miles north of Hampshire.

And one can only assume it was the weather, and possibly desperation, that caused Mary to enter the St. Giles dwelling-house of William Dean on that cold and windy day.

The wrong side of town?

The West End of London in 1810, with its palaces, houses of parliament and theatres, was home to a well-heeled population. Was Mary a native of the West End, or just visiting with the intent of taking advantage of the affluence of the West End’s residents? Either way, Mary’s presence in the home of William Dean was probably not opportunistic. A set of ‘false keys’ reportedly found in Mary’s possession, adds substance to the supposition of a premeditated act.

Between the hours of two and three in the afternoon, Mary was in an upstairs bedroom of William Dean’s dwelling-house, allegedly availing herself of a number of items including “a pair of sheets worth 10 s. three shirts, worth 5 s. three neck handkerchiefs, worth 1s. a hat 3 s. a pair of boots, half a crown, and a great coat, 10 s.” (Old Bailey Proceedings)

As Mary was stuffing the items into a bag, she was suddenly interrupted by the sound of a key in the door.

Caught red-handed

Being caught in the act was surely not part of Mary’s plan, and if it hadn’t been for William Dean’s son needing to retrieve a hat from his bedroom, Mary may well have made good with her escape long before anyone noticed anything missing. Instead of lugging home her bagful of loot, Mary was escorted empty-handed to Newgate Prison, where she awaited her trial.

Standing alone in the Old Bailey, Mary Cavillon, born Mary Lyons, heard the word death uttered when her sentence was read out. Her first thoughts must surely have been for her children and what would become of them. But life has a way of changing direction when you least expect it, and on the 10th August 1811, Mary received a pardon through the benevolence of the Prince Regent, and she was free to go. Either Mary stayed out of trouble for the next three years, or she successfully played the artful dodger, because no mention of her name has been found in the intervening years.

Another day in court

Sadly, in 1813, Mary must have stood in the dock of the Old Bailey for a second time. While no court list bearing her name has been found, evidence of a punishment meted out to her is well documented. It seems Mary may have conjured up an alias when caught in the act of a crime so like her previous one, that it is compelling enough to believe she did face the judge that day. The circumstances of the crimes of Mary Cavillon and Isabella Phillips, three years apart, are almost identical, despite a discrepancy in the recorded ages of the women. No evidence has been found to support this, but historians have documented the possibility.

Regardless of the name, Mary (or Isabella) was again given the death sentence, only to have it changed to a ‘life sentence in the colony of New South Wales’. Mary was to sail on the Broxbornebury the following February with one hundred and twenty-four other female convicts.

The women on the Broxbornebury seemingly made the most of the long journey. Jeffrey Hart Bent, soon-to-be Judge of the Colony, noted in his journal that around teatime on Thursday 24th March, having passed Tenerife in the Canary Islands earlier in the day, convicts and settlers danced and sang on deck to the tune of the piper, ordered to play for them by the captain.

What compels us to believe that Mary was on the Broxbornebury is the name of her thirteen-year-old son, Nicholas Cavillon, listed on subsequent records. But regardless, Mary’s name is etched into the history of New South Wales as a convict, from 1814 until her death in 1832.

the Female Factory

While no evidence has been found to support it, one can assume that Mary was assigned to the Female Factory at Parramatta, as many of the female convicts and their children were. In 1814, the Female Factory was simply an extension to the Parramatta Gaol, prior to a significant upgrade in 1818.

Mary’s fate changed when her son Nicholas, then a successful baker, turned twenty-one in 1822, and Mary was assigned to him for the remainder of her life sentence. Whatever drove Mary to a life of crime in England, seems to have escaped her in the new colony because Mary’s name appears only a few times in convict records, and not for breaches of behaviour, although the use of an alias and various spellings of the name Cavillon, may have impeded the search for documents.

Nicholas Cavillon married Milbah Harrax in 1829, so it is supposed that Mary lived with Nicholas and Milbah until her death. Sadly, it seems that Nicholas’ drinking, fuelled violent behaviour towards Milbah. Was Mary witness to the violence? Did her convict status prevent her from intervening? And what must Mary have thought when Nicholas was imprisoned for three years for attempting to sever Milbah’s ear in a drunken fit of rage? Had Mary suffered abuse in her own marriage?

Mary’s marriage to Nicholas Francis Anthony Cavillon in 1792 is documented, and she bore four children to him. Nicholas was the youngest, which might be why he accompanied Mary on the Broxbornebury, and the older children stayed in London.

Freedom

In 1832, death released Mary from the confines of her convict life and the imaginable pain of abandoning her older children. She finally earned her freedom.

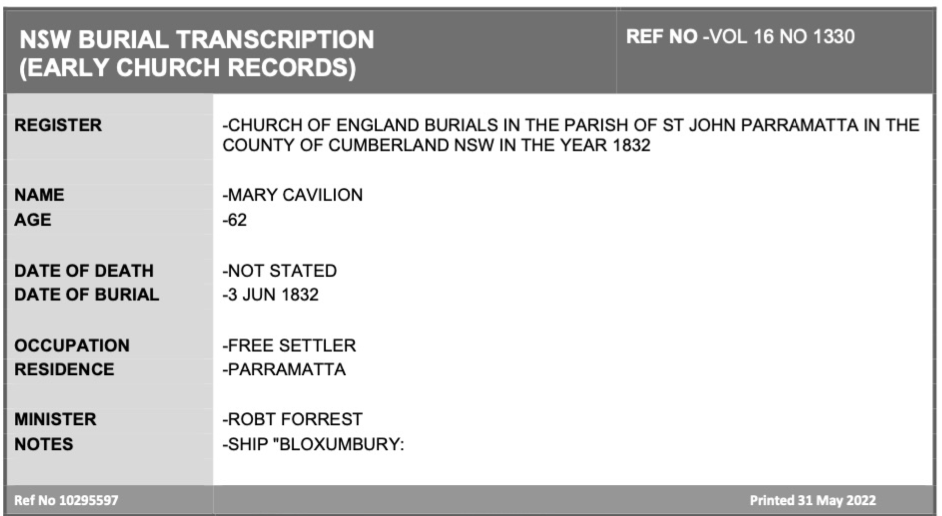

Perhaps it was a mark of respect that Nicholas made no mention of Mary’s convict status on her death certificate, but rather stated that she was a Free Settler.

When Nicholas died in 1869, he was buried with his mother.

Mother and son, together in life and death.

Reflection: Dates throughout were difficult to ascertain given the aliases used by Mary Cavillon. Mary was the mother-in-law of my 1st cousin 4x removed, Milbah Harrax, who married Nicholas Cavillon in 1829.

Bibliography

Ancestry.com.au.

Australian Royalty, Mary Cavillon, 1770-1832.

Bent, J.H., Journal of a voyage performed on board the ship Broxbornebury, Captain Thomas Pitcher, from England to New South Wales, 1814 [manuscript],

Cameron, M.A., Mary Cavillon: Homemaker, Housebreaker, St. John’s Online, 2021,

Cameron, M.A., Nicholas Cavillon: A Hardened Villian

Commercial Journal and Advertiser (Sydney, NSW : 1835 – 1840), 13 November, 1839 p. 3.

Commercial Journal and Advertiser (Sydney, NSW : 1835 – 1840), 26 February, 1840, p.2.

Death Certificate, transcript obtained by author, 2022.

England & Wales, Criminal Registers, 1791-1892, England, Middlesex, 1810, p.18, in Ancestry.com.au.

England & Wales, Non-Conformist and Non-Parochial Registers, 1567-1936, Victoria

History of the West End of London,.

Index to the Colonial Secretary’s Papers, 1788-1825, Ship: per “Broxbornebury”, online search: Cavillion, Citation: [4/1836B], File No.177, p.817 | Start Date: 29/08/1824.

Newgate Calendar of Prisoners, London, England, 1785-1853 for Mary Cavillon, in Ancestry.com.au.

NSWBDM, Marriage Certificate, Cavillon & Harrax, 4491/1829 V18294491 3B.

NSW State Archives & Records, Convicts Index 1791-1873, Ship: Bloxenbury | Citation: [4/4549; Reel 690 Page 034] | Record Type: Convict Death Register | Date: 03/06/1832.

NSW State Archives & Records, Female Factory, Parramatta,

Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 20 June 2022), June 1813, trial of ISABELLA, alias ELIZABETH PHILLIPS, (t18130602-100),

Old Bailey Proceedings Online, (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 19 June 2022), December 1810, trial of MARY CAVILLON (t18101205-33).

The Gallery of Natural Phenomenon

Westminster, London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1935,